From left to right: original red livery (1968-1972), 1970s livery (1972-198X), blue fronts without air conditioning (1988-199X), final livery (1989-1999) and the 4th batch trains in the same latter three versions.

DOWNLOAD

All the necessary dependencies are either included in this package or are avaible on the DLS. Soundscript by Rizky_Adiputra.

(Consists are included! Don’t bother with placing individual cars!)

This is of course a reasonably well-known train as far as trainz content goes, having been made countless times in almost evry sauce. However, nearly all Toei 6000 Series models have been made from an “Indonesian” perspective, with the train being modelled as it was in service in Indonesia (with all related fetaures such as cowcatchers and window grills) and then eventually “back-modelled” into a Japanese version. This time around, i wanted to make the opposite – modelling from the “Japanese perspective” to properly encompass all the slight variations these trains had during their service life.

Now, depsite it’s unassuming appearance, the Toei 6000 Series has quite a tricky and intersting history, indissolubly connected to the one of it’s line – the Mita Line, wich has always been one, if not the one with the most difficult upbringing among all of Tokyo’s subway lines, wether TRTA or Toei ones.

What is today’s Mita Line was originally planned in 1957 as two different lines, one being a replacement for serveral tramway lines, intended to function as a branch of the Asakusa Line (and as such adopting the Asakusa Line’s 1435mm standard gauge) and the other as a northern branch of the Tozai Line, wich would’ve been operated by TRTA and would’ve eventually reached Toda in Saitama Prefecture (ideally to serve a boat racing venue of the 1964 olympics).

In 1962 the subway master plan was revised, with the two branches being merged into a single line, numbered as Line 6, and planned to run between Gotanda, Itabashi and Takashimadaira, wich at the time was a rural zone being built up into a very dense cluster of Danchi apartments, Japan’s typical apartment blocks (inspired from Soviet practices) that shaped urban expansion thruought the Japanese economic miracle.

Since the southern section was to be shared with the Asakusa Line to reach Nishi-Magome depot, Toei kept the 1435mm gauge in it’s plans for Line 6, however soon both Tokyu and Tobu railway intervened, strongly demanding that Line 6 connect to their respective networks, since the line’s planned terminuses were directly adjacent (such as in the case of Gotanda station for the Tokyu Ikegami Line) or within short distance from some of their main stations (Takashimadaira was a few kilometers away from Tobu’s Wakoshi station), thus forcing Toei to redraw it’s plans and to opt for the 1067mm gauge instead, making Line 6 incompatible with the Asakusa Line.

Tokyu Railway dropped out relatively soon from these plans, since their primary objective was to connect the Denentoshi Line to the subway network, ideally to the Ginza Line, even if it meant adopting a third rail (ultimately the Denentoshi Line began trough-services with the Hanzomon Line in 1978, built as a relief and bypass of the overcrowded Ginza Line).

However, Toei continued building Line 6, and was preparing for trough-services with Tobu, specificially with the Tojo Line – the ATS system was built to be compatible with Tobu’s, and the subway rolling stock was to follow Tobu standards, including the provision of a raised driving position as a saftey mesaure against collisions at level crossings.

The first batch of these such trains, fourteen 4-car sets classified as the 6000 Series were built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries with electrical equipment from Hitachi, and were delivered in early 1968 to commence test-running on the nearly-finished infrastructure of the line.

Toei’s sleek new stainless-steel trains were a true step-up from coeval rolling stock, however depsite their unassuming technical equipment and standard fittings, the 6000 Series was the bearer of a small, but fundamental revolution, being one of the first mass-produced trains fitted with an SIV, a static inverter.

Now, to power passenger compartment lighting (and other fetaures), a so called “low-voltage” (or “auxiliary”) electrical circuit is used, with a voltage usually between 12 and 440V DC, powered by the train’s auxiliary batteries (wich are continuously recharged by the catenary while the pantograph is up). However, having a DC circuit means that the powered equipment (such as lights) has to be DC as well, meaning it needs to be specialized (as most of it is produced for the house mains of 100V AC), and thus relatively expensive. A Static Inverter instead is an inverter that indeed converts DC to AC current, (unlike the traction inverters that would be widely adopted two decades later, SIVs only have a single output frequency) meaning that the auxiliary circuit for the lighting and interiors could be converted to the same 100V AC current of Japanese house mains, enabling manufacturers to utilize commonly available and mass-produced household-like equipment such as lightbulbs, driving down costs and making spare parts easier to source.

With this small but fundamental revolution, something that has been standard since on all kinds of rolling stock, the 6000 Series was awarded the 1969 “Laurel Prize” by the Japan Railfan Club.

For the planned trough-services with Tobu Railway, the 6000 Series had been fitted (besides the afromentioned raised driving position) with an additional service type indicator above the driver’s window and the top destination rollsign was also already fitted with some Tobu Tojo Line station names: Wakoshi, Shiki, Kami-Fukuoka, Sakadocho (currently Sakado), Hgashimatsuyama and Shinrin-Koen, the northernmost terminus of most Tojo Line services.

Livery-wise, the 6000 Series was left unpainted, except for a thin dark red line on the sides, then the colour of Toei’s rolling stock (both lines of the Toei Subway and also of the surface Toden tram network and Toei busses as well).

Finally, the first section of the Line, from Sugamo to Takashimadaira opened on the 27th of December 1968, with 6000 Series trains entering revenue service on the same day. This portion was isolated from the rest of the subway network (both Toei’s and TRTA ones), and initially only acted as a feeder to the Yamanote Line, wich it connected to at Sugamo.

However, even as the northern portion of the line opened to the public, Tobu still hadn’t bothered to start construction for their branch line from Wakoshi station to Takashimadaira, where it would have connected with the Mita line.

Tobu was getting second thoughts, partly because the Mita line took a slightly circuitous route to central Tokyo, but also because it wouldn’t pass through Ikebukuro – Tobu had their terminal there, and thus, like most japanese major private railways had a significant commercial presence. Having direct trough-services between the Tojo Line and the Mita line would have given passengers a more direct link to shopping areas in central Tokyo, such as high-end Ginza, effectively self-hurting their own department stores businness in Ikebukuro.

Around the same time, the president of Seibu Railway, which also had a major railway line terminating in Ikebukuro, used his considerable financial and political power to change the planned route of what would later become the Yurakucho line to pass through Ikebukuro, and to evenutally connect with the Seibu Ikebukuro line.

As soon as this change was finalized and approved Tobu jumped ship, announcing their intentions to connect the Tojo line to the Yurakucho line as well (in what would eventually become the intricated mess of the Yurakucho and Fukutoshin Lines), and basically told Toei to go screw themselves.

Toei (and thus by extension, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government) predictably protested vociferously, but the national government told them to stay put.

As a result, Toei was left with a subway line that was fully compatible with a commuter line that it was intended to connect to, but remained orphaned of trough-services possibilities at both ends of the Line.

Depsite this, Toei Subway soldered on, remaining open for eventual trough-service openings. The Mita Line was extended southwards to Hibiya on the 30th of June 1972, ending the “temporary isolation” to the line and it’s proper integration into the Tokyo subway network. For this extension another batch of 6000 Series trains, built by Alna Koki and Nippon Sharyo with Hitachi equipment, formed as nine 6-car sets plus an additional 28 cars to lenghten the 1968 1st batch trains to six cars as well.

These new second batch trains fetaured a few improvements and changes – first of all, Toei (having gave up any hope for a start of trough-services with Tobu railway within reasonable time) had the new batch delivered with rollsigns devoid of Tobu station names. Secondly, the new trains were still unpainted stainless, but with a blue line instead, having been choosen as the Mita Line’s colour to distinguish it from other subway lines.

The two liveries mixed up for some time, and for a brief period it was possible to spot “mixed formations” two “blue” 2nd-batch cars sandwitched in the middle of a 1st-batch “red” formation. Eventually within a year, all trains were repainted into the Mita Line blue livery (and Tobu station names were all removed from rollsign at the first scheduled maintainance).

On the 27th of November 1973 the line reached it’s namesake Mita Station, the interchange with Toei’s other subway line, the Asakusa Line. For this extension, another batch of 6000 Series trains was delivered, formed as three 6-car sets built by Alna Koki and essentially identical to 2nd batch ones built a year earlier.

Finally, on the 6th of May 1976 the last extension of the line opened, from Takashimadaira to Nishi-Takashimadaira (a section that originally was intended to be part of Tobu’s connecting line and was as such originally licensed to Tobu railway, before being transferred to Toei at a later date). For this extension, a 4th (and final) batch of 6000 Series trains was delivered, formed as two 6-car sets built by Alna Koki.

This latter batch was of a more simplified design than it’s predecessors, with the main tell-tale fetaure being the lack of door pocket windows, something derived from the 5200 Series of the Asakusa Line that was being built at the same time (coincidentally as a batch of two six-car sets as well), giving them a more distinctive look.

The one to Nishi-Takashimadaira would end up being the last Mita Line extension for a relatively long time. Preparatory work for an extension towards Sengakuji (part of the original “Asakusa branch line” plans) was begun, but left incomplete shortly after, and in 1985 the Ministry of Transportation finally ordered Toei to shelve all plans for a northwards extension of the line to Saitama (something that had been around since the original 1957 plans for a northwards branch of the Tozai Line) due to the opening of the Saikyo Line.

Shortly after, in 1988, the Mita Line 6000 Series began to be slightly repainted, with the stainless steel front being modified with the addition of front blue bands around the headlights (wich would end up as a distinctive fetaure of these trains), in order to help users distinguish them from other unpainted stainless steel rolling stock (such as Hibya Line trains).

A year later, in 1989 Toei finally proceeded to retrofit all 6000 Series trains with air-conditioning units (wich was carried out by Keio Heavy Equipment Maintainance Co., a subsidiary of Keio Railway), and at around the same time all trains were fitted with the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s (and by extension, Toei’s) “gingko leaf” green logo on the front doors.

However, unexpectedly, by the early 1990s something started to “move” in regards to the trough-services Toei had long craved for, with the Transportation Bureau managing to piggyback on the exension plans of TRTA’s Namboku Line to Meguro, where it would’ve connected to the Toyku Meguro Line.

Toei managed to score an agreement with TRTA, that the new Namboku Line section from Tameike-Sanno to Meguro would’ve joined by the Mita Line at Shirokane-Takanawa, and jointly operated from there to Meguro.

Originally, Toei intended to adapt and modify it’s 6000 Series trains, however it immediately proved difficult, especially considering that the extension to Meguro was to be built to Namboku Line standards, fetauring platform screen doors and semi-automatic ATO operation. To adapt 6000 Series trains would’ve meant performing extremely expensive modifications, possibily even double the price of a new rolling stock purchase, something that made no economic sense, considering that the 6000 Series was now reaching the end of it’s service life, and compared to coeval rolling stock, was now relatively obsolete, depsite still performing well it’s duties.

In the end, plans to use the 6000 Series were almost immediately shelved in favour of a more rational purchase of new rolling stock, to be built already compatible with the new section’s standards.

Classified as the 6300 Series, a first small batch of five of the new Mita Line trains was introduced in regular service in 1993, replacing the most worn-out 6000 Series units, followed by a second batch of eight sets a year later in 1994. 6300 Series were then temporarily suspended due to the necessity to retify, uniform and standardize the performance and equipment of the new trains with TRTA’s 9000 Series. With these issued being solved, a bulk older of an additional 24 sets was made to finally replace the 6000 Series, with the last run of the Mita Line’s original trains held on the 28th of November 1999, ending 31 years, 11 months and one day of reliable and faithful service.

A year later, on the 26th of September 2000, the 32-years-long isolation of the Mita Line was finally ended with the commencment of trough-services with the Meguro Line.

In the end, the Toei 6000 Series had a quite unlucky history, but unexpectedly, after their retirement, things soon took a turn for the better.

The sudden large surplus of well-built, reliable and most importantly already air-conditioned trains available for relatively cheap prices made the 6000 Series appealing to many third-sector rural railways, an exceptional case with Toei rolling stock (wich is rarely purchased second-hand due to the extensive wear and tear it suffers during it’s intensive service life), with two railways, Chichibu Railway and Kumamoto Railway purchasing conspicuous fleets of the retired trains (four 3-car sets in the case of the former and five 2-car sets in the case of the latter).

However, the true turn in the 6000 Series’ history came in 2000, when eight six-car sets plus an additional 24 intermediate cars (to be rebuilt locally into proper EMUs) were donated free-of-charge by Toei to Indonesia, as part of an official development assistance campaign promoted by the JICA (the Japanese Government agency for international cooperation), where they would’ve been used to revive the fortunes of Jakarta’s Jabotebabek commuter rail network, wich had fell in decay and disrepair at the time.

Not only the 6000 Series brought a breath of fresh air (both figuratively and literally, thanks to their air-conditioning!) to the KRL Jabotebakek commuter system but also spearheaded a comprehensive reorganization of the network, from countless point-to-point services to a rational line-based system, and of the general operations as well, among other things, under the maintainance aspect changing from a “repair when broken” system to proper pre-emptive maintainance.

Originally introduced on special “Expess” service where a fare surcharge applied, the 6000 Series opened the doors for the import of more and more used rolling stock bought second-hand from a variety of sources, wich led to the replacement of the old dilapdated rolling stock with comfortable air-conditioned trains and the progressive transformation of the Jabotebabek network into a modern and efficient commuter rail system.

However, age soon catched up with the 6000 Series trains, as they too started to be replaced by the copious introduction of ex-JR East 205 Series trains, with the last indonesian 6000 Series being retired in 2016.

Out of 168 vehicles built, 96 (more than half) were donated to Indonesia, 12 were bought by Chichbu Railway and converted into 5000 Series trains (of wich three out of four still are in operation as of today) and 10 were purchased by the Kumamoto Railway and converted into 6000 Series trains (of wich two out of five are still operating), resulting in a total of 118 cars escaping scrapping in Japan, plus two additional intermediate cars that were also saved and are now currently on display in a pubblic park in Chiba and the front half of a cab car that was transferred to the Tokyo Fire Department as a (“very B-train shorty-esque”) training facility.

Out of the indonesian sets, wich began to be scrapped after their retirement in 2016, a cab car was preserved and it’s now on display inside KAI Commuter (KRL Jabotebabek’s successor) Depok depot.

In the end, depsite their intial unlucky history, the 6000 Series saw an interesting turn of tables, going from an unassuming and utilitarian subway train to something quite famous and well-known, likely even more so in Indonesia rather than Japan.

Trivia #1

The start of trough-services with the Meguro Line not only spelt the end for the 6000 Series, but for conductors on the Mita Line as well, as since the full replacement of the 6000 Series, all trains on the Mita Line have been driver-only-operated (exactly like the Namboku Line with wich the Mita Line shares tracks).

Trivia #2

6000 Series trains in the “1970s” unpainted fronts blue livery are fetaured in the 1975 movie “Shinkansen Daibakuha” during a chase scene unfolding thruought the Mita Line’s Shimura depot and adjacent Nishidai station.

Bonus video #1

Due to their unassuming nautre and “out-of-the-way”ness, videos of 6000 Series trains in service on the Mita Line are relatively scarce – here’s one of the few rare ones, depicting the final service years of these trains in the mid to late 1990s.

Bonus Image #1, from this nice website depicting the early days of the Mita Line

January 1969, a month after the opening of the Mita Line, this was mostly the landscape it ran trough – barren land ready for development, with nothing in sight for kilometers.

The station in the picture is Nishidai, looking from the south side of the line (more or less where Takashima-dori currently is). In a few years the area will be ripe with high-rise buildings and Danchi apartment blocks.

Bonus Image #2

It’s quite hard to see, but this is one of the very few pictures taken of the “mixed livery” formations that briefly existed in 1972, when the original 1st batch red-coloured trains were lenghtened to six cars sets with intermediate cars already painted in the new Mita Line blue livery.

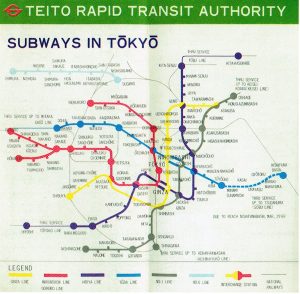

Bonus Image #3 – a Subway Map pubblished by TRTA in early 1969 shortly after the opening of the Mita Line.

The two Toei Subway lines (dark grey and very, very light blue) are correctly named as “No.1 Line” and “No.6 Line” – both lines will get their proper names (“Asakusa” and “Mita” respectively) only in 1978, shortly before the opening of Toei’s third subway line – Line No.10 – the Shinjuku Line. The Mita Line will also remain isolated from the rest of the subway network until 1972, when the extension to Hibiya was opened.

(also note the “Ogikubo Line” moniker under the Maronouchi Line – “Ogikubo Line” in this case refer to the trackage west of Shinjuku, both the main line and the Honancho Branch line, as opened in 1962. The Ogikubo Line was seamlessly operated jointly with the Maronouchi Line, with the same rolling stock, and there was effectively no difference between the two – the separate name was basically only bureaucratic matter. In the end, in 1972 the Ogikubo Line was merged into the Maronouchi Line, ceasing to exist).