The first plans for a subway system in Madrid came about in the late 1880s – already ten years after the introduction of horse-drawn, and later steam-hauled tramways, the intensity of their traffic trough the cramped city center was already so high that various abortive proposals to relocate tramways underground, or replace them altogheter with an underground railway modelled on London’s underground system started being made, both in an official and unofficial capacity.

However, it was only at the beginning of the 1910s that serious projects started being made, chiefly thanks to the work of three engineers: Miguel Otamendi, Carlos Mendoza and Antonio Gonzalez Echarte. The envisioned network, as otulined in the plan submitted for royal assent in 1914, called for the construction of four lines with a combined lenght of 154 Km. Royal Assent to the project was granted on the 16th of September 1916, with the three engineers now needing to raise the necessary 8 million pesetas capital to build the system. This turned out to be harder than expected, with most financial institutions being unwilling to bankroll the project, deeming it “interesting” but “too premature”, meaing unneccessary. Only the Bank of Vizcaya agreed to fund half of the projected cost, with the condition that the three engineers raise the other half. The three were able to raise about 2,5 million pesetas from the pubblic and with King Alfonso XIII, wich by then had taken a keen interest in the project, stepping in to cover the remaining 1,5 million needed with his own finances.

With the necessary capital raised, the “Compañía Metropolitano Alfonso XIII” (“Alfonso XIII Metropolitan Railway Company), named in honor of the most notable financier of the project, the king himself, was officially formed on the 24th of January 1917 and construction began on the first line of the system, between Sol and Cuatro Caminos, on the 23rd of April of the same year.

Construction was completed in early 1919 and on the 17th of October the first section of the Madrid Metro, running between Sol and Cuatro Caminos, with eight intermediate stations and a distance of about 3,5 Km was officially inaugurated by king Alfonso XIII.

The success of the Metro was considerable, with 14 million passengers using it already within it’s first year of operations. In 1921 the line was extended southwards to Atocha, and on the 14th of June 1924 a second line (Line 2) was opened, running east-west from Sol to Ventas, being soon extended northwards from Sol to Cuatro Caminos, on a roughly parallel alignment to Line 1. In 1925 an unforseen addition to the 4-line masterplan was made – a shuttle service (“Ramal”) connecting Isabel II (currently Opera) station on Line 2 to the Estacion del Norte (currently Principe Pio) railway station.

In 1931, with the proclamation of the Spanish Repubblic, all references to royalty in pubblic places and services were removed, with the “Compañía Metropolitano Alfonso XIII” being renamed as the “Compañía Metropolitano de Madrid” or CMM (likewise, Isabel II station on Line 2 was renamed to the current “Opera”).

In the early 1930s two more lines were added to the network – Line 3 from Sol to Embajadores and the initial section of Line 4 from Goya to Diego de Leon, initally operated as a branch of Line 2. The subsequent spanish civil war led to all extension works cancelled, with the metro initally repurposed as a bomb shelter, and later was used to evacuate repubblican battlefield casualties to hospitals as francoist troops laid siege to the city. With the defeat of the repubblic, and the instauration of the fascist falangist government, with Francisco Franco as it’s undisputed dictatorial head, subway expansion gradually restarted, but at a much diminished pace, especially due to the increasing economic woes of the Madrid Metro company. The original 1914 masterplan was functionally completed in the early 50s, with the completion of Line 3 from Arguelles to Legazpi and the construction of the east-west Line 4 from Arguelles to Diego de Leon, absorbing the already-built section between Diego de Leon and Goya.

At the same time, with the original project completed, the city council of Madrid started envisioning a new plan, wich called for the construction of suburban metro lines, technically identical to the “urban metro lines” (using the same 600v DC overhead power supply, 1445mm gauge and same narrow-profile rolling stock) but with much longer intra-station distances and on a surface, rather than underground alignment. Of the lines planned, only one would see the light of day – the aptly named “Suburbano” (“Suburban”) line, a “hook-shaped” line running in a south-westerly direction between Plaza de España (interchange with Line 3) and Clarabanchel, opened in 1961 and owned not by the Metro, but by a separate company – the Ferrocarril Suburbano de Clarabanchel a Chamartin de La Rosa (“Clarabanchel-Chamartin de La Rosa Suburban Railway”) and operated by “Explotacion de Ferrocarril de l’Estado” (“State Railway Operator” or “EFE”), the state-owned company responsible for operating Spain’s narrow gauge railways, wich would become “FEVE” in 1965. Also at the same time, with the financial situation of CMM gradually worsening, making the company unable to finance any network expansion, the infrastructure of the Metro was functionally “nationalized” with CMM remaining responsible for operating the metro, providing rolling stock and all the other necessary equipment – from now on, the state would be the one financing and building extensions.

The most notable of these “state-funded” expansion was the construction of Line 5, inaugurated in 1968 from Callao to Clarabanchel inheriting the right-right-of-way of one of the “suburban” metro lines of the abortive early-50s plan, being later extended in 1970 to Ventas, interchange station with Line 2 and taking over the latter’s north-eastern leg from Ventas to Ciudad Lineal.

Line 5 would end up being the last Madrid Metro line built to the Paris-like narrow-profile – as part of a major extension plan approved in 1967, the envisioned lines (similar to today’s lines 6, 7, 9 and part of Line 10) were to be built to a much wider and larger loading gauge, closer to the one that had been in use in Barcelona on it’s Lines 3 and 5, in anticipation of larger passenger volumes. The first of these such “wide-profile” lines, Line 7, was opened in 1974 initially as a feeder for Line 5, running between Pueblo Nuevo and Las Musas.

By then however, the functional divorce between state-mandated expansion and a chronically insolved CMM, unable and unwilling to keep up to the financial investments demand, chiefly in terms of rolling stock, had led to a relatively dire situation and a serious rolling stock shortage, both on the new wide-profile lines (whose fleets had been deliberately undersized to save money) as well as on the larger narrow-profile lines, with the “original” lines 1 to 4 still operating with the same trains they were inaugurated with, especially on Line 1, wich was still running the same 50-year old rolling stock it had opened with in 1919!

Thing started to change in the late 1970s when, after Franco’s death, the newly-democratic Spanish government directly intervened in 1978 by adopting a special funding and renewal plan and by placing CMM under close supervision by a dedicated committe of administrators nominated by the ministry of transportation.

The “Special Maintainance, Improvement and Investment” plan, as promulgated by decree law 13/1978, placed a temporary halt to planned network expansions in favour of the much-needed refurbishment of the oldest lines, procurement of additional rolling stock for the wide-profile lines and of replacement trains for the narrow-profile network. Lines already under construction at the time were however completed, with the initial sections of Line 6 from Cuatro Caminos to Pacifico, Line 9 between Sainz de Baranda and Pavones and Line 8 from Nuevos Ministerios to Fuencarral being opened thruought the early 1980s.

As Spain further democratized, a system of devolved regional governments with considerable autonomy in a number of sectors, among wich regional transit, was devised, with Madrid and it’s Metropolitan Area forming the “Community of Madrid” in 1983. As part of the newly-devolved powers in transit planning and financing, the Community of Madrid formed the “Consorcio Regional de Transportes de Madrid” (“Madrid Regional Transportation Consortium”) in May 1985 as an authority in charge of planning transit expansion, coordinate all the operators concerned and administer “in detail” regional funding.

With the agency’s creation, on initiative of the community of Madrid and with the assent of the central government, the Madrid Metro was immediately entrusted to CRTM, with the “oversight committe” that had steered the system on behalf of the central government since 1978 being disbanded. As such, the Madrid Metro was finally brought under full pubblic ownership on the 31st of December 1986, ironically “nationalized” by the regional government.

Under the auspices of CRTM and with additional funding available (thanks to the booming economy as a direct consequence of democratization), network expansion resumed at a considerable rate, with Line 9 being extended to Herrera Oira, and Line 6 getting closer to forming it’s final loop shape and the old Clarabanchel suburban line being finally taken over from FEVE and integrated into the metro network as Line 10.

In 1989, the 70th-birthday year of the Metro, the system was spun-off from CRTM and transferred to the dedicated pubblicly-owned “Madrid Metro S.A.” company that has been operating the system to this day (altough still under CRTM supervision and directions). The circular Line 6 was completed in 1995 and in 1998 and Lines 10 and 8 were “joined” with the former absorbing the latter, with a “new” Line 8 serving the fairgrounds (Feira de Madrid) being opened six months later.

The latter half of the 1990s were fruitful years for Madrid Metro, as Madrid political candidates made metro expansion a centerpiece of their electoral programs. As a result of this, numerous lines and extensions were built and opened within a narrow time frame: Line 11 from Plaza Eliptica to Pan Bendito, the extension of the “new” Line 8 to Madrid-Barajas airport, the southeast extension of Line 1 and the northeast extension of Line 4, the western extension of Line 7, bringing it from a relaitvely isolated feeder to one of the trunk lines of the network and most notably, the extension of Line 9 to Arganda del Rey along a regional-railway like alignment with extremely long intra-station distances – this latter “suburban” segment being owned by the “TFM” (Transportes Ferroviarios de Madrid – “Madrid Railway Transportation”), a private consortium with Madrid Metro and local authorities as shareholders.

The breakneck expansion continued well into the early ‘2000s, with Line 10 being rebuilt to the wide-profile standard of newer lines and the extension of Line 8 to Nuevos Ministerios. The most important project of this time however is undoubutedly the “MetroSur” – Line 12, a fully-underground 40km-long feeder loop line serving a “crown” of commuter towns in the southern outskirts of Madrid and connecting them to the rest of the metro network (altough for the moment only with Line 10!) and most importantly, with the RENFE-operated Cercanias commuter railway network.

Finally, going even higher, the most ambitious expansion ever was carried out between 2003 and 2007, with nine of the thirteen metro lines being extended further outwards into the Madrid outskirts, with northern extension of Line 10 to the Hospital del Norte (“MetroNorte”), an eastern extension of Line 7 to Hospital del Henares (“MetroEste”) and perhaps most notably, the inauguration of three “Metro Ligero” (“Light Metro”) lines – these being (despite the name) light-rail standard modern tramways operated by Alstom Citadis rolling stock – Line ML1 connecting Pinar de Chamartin (terminus of Lines 1 and 4) to Las Tablas (Line 10) and Lines ML2 and ML3, branching out from Colonia Jardin station on Line 10 and serving the western outskirts of Madrid.

This expansion bonanza, wich had grown the network to nearly 300 kilometers in lenght, making it the second longest in europe behind London, however came to an abrupt end with the 2008 financial crisis and it’s subsequent fallout on the european union, precipitating a recession and the subsequent european sovereign debt crisis, wich hit Spain particularily hard, with the country, having relied mostly on debt to finance infrastructure expansion (to wich the massive madrid metro expansion was part of, togheter with the equally massive AVE high-speed network expansion) risking a default.

In subsequent years, as the spanish economy recovered from the crisis, further expansion to the now largely adequate Metro network were put on hold, with only few extension opening since, the lastest of wich being the one-stop northern extension of Line 9 from Mirasierra to Paco de Lucia.

As of today, Madrid’s metro network is formed of thirteen “full subway” lines (1 to 12 and the “Ramal”) and three “Metro Ligero” light rail lines, with the two systems totalling 293,3 km long in lenght and serving 330 stations.

Metro expansion has been greatly toned down, as the network is now effectively at an “adequate” lenght for the city’s needs – the only currently ongoing major projects are the southern extension of Line 5 from Villaverde Alto to El Casar, providing a second “Metro-Metro” connection to Line 12 and the northern extension of Line 11 to Atocha, with the eventual goal of extending it all the way to Chamartin on an eastern tangential alignment – restructuration, refurbishment and upgrade of existing lines, such as the automatization (with driverless trains) of the circular Line 6, the busiest in the network, and the gradual catenary voltage increase, from 600v to 1200.

Trivia #1:

As a way of containing costs, and also due to the difficulty in acquiring new equipment due to the ongoing first world war, the Madrid Metro Company in it’s infancy opted to acquire second-hand stuff as much as possible, especially rolling stock components: the bogeys were acquired from withdrawn tramcars all over Spain, and traction motors were bought from Paris Metro spare part stockpiles.

Trivia #2:

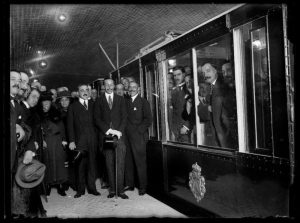

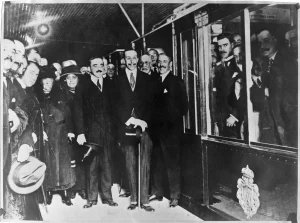

The official photo for the 1919 inauguration of the Madrid Metro, with King Alfonso XIII, head of state and one of the Metro’s principal financial supporters, front and center (with the walking cane and top hat in hand).

A little hiccup with this photo was only noticed when it was being developed, long after the inauguration had ended: the king had been inadvertently photographed in the split-second when he had his eyes closed!

Unable for obvious reasons to take another picture, the newspaper editors had to resort to “edit” the picture and paint eyes on the face of the king!

The original photo on the left, with the king’s eyes closed, and on the right – the edited photo as it appeared on newspapers.

Trivia #3:

For the construction of the system, the three engineers had sought and recieved royal assent and ministerial approval, but did not have, nor requested, construction permits to the city of Madrid, considering the former two to be regardless valid due to their “hierarchical higher” status, and crucially, as part of this, the Madrid Metro company had not been paying to the city any land usage taxes. This “overstepping” of municipal power did not sat well with the city council, wich started rowing against the whole project, even after the first section had been inagurated.

One of the most notable incidents from this period of animosity is the March 1922 confrontation between the Madrid Municipal Police, wich had been sent to stop construction works on the Line 1 extension from Sol to Atocha, and the Guardia Civil and National Police called in to “protect” the site. The subsequent clash led to the Guardia Civil actually arresting a number of municipal police officers (!), as well as the vice-mayor that had sent them (!!) and ultimately resulted in the sacking of the then-mayor, Álvaro Figueroa y Alonso-Martínez, Marquess of Villabrágima and his replacement with José María de Garay y Rowart, count of the Suchil Valley.

Trivia #4:

The late-90s expansion program brought the addition of 170 km of metro lines to the network in only about five years. This expansion rate, rivalled only by Seoul at the time, was recognized as one of the largest and most important pubblic works projects, not only in Spain, but in the whole of Europe.

Part of this success was also thanks to the streamlining of construction costs to about 31 million euros per kilometer, a comparatively low price for a full-sized subway (for reference, London’s Jubilee Line extension, being built at the same time, costed ten times as much per kilometer).

Trivia #5:

Also part of the late 90s expansion program, at one point six different tunneling boring machines were in operation at the same time under Madrid, with one, built by Mitsubishi, achieving the speed-boring record of 792 meters of tunnel dug in just one month.

Narrow-Profile Lines

Line ![]() , Line

, Line ![]() , Line

, Line ![]() , Line

, Line ![]() , Line

, Line ![]() , Line

, Line ![]()

Wide-Profile Lines

Line ![]()

Line ![]()

600v DC rolling stock, July 1974-September 2006 (section from Las Musas to Pitis only)

Line ![]()

Narrow-Profile rolling stock (section from Mar de Cristal to Barajas only), June 1998-December 2001

Line ![]()

TFM Section (“Line 9B” – Puerta de Arganda-Arganda del Rey)

Line ![]()

Narrow-Profile rolling stock (section from Fuencarral to Aluche only), December 1991-August 2002

Line ![]()

Wide-Profile rolling stock, 600V DC (section from Plaza Eliptica to Pan Bendito only), November 1998-October 2000

Narrow-Profile rolling stock, 600V DC (section from Plaza Eliptica to Pan Bendito only), October 2000-December 2006.

Former lines

Line ![]() “Old”

“Old”

Section from Nuevos Ministerios to Avenida de America, absorbed into the current northern leg of Line 10 in late 1997.

Wide-Profile rolling stock (June 1982-December 1997)

Narrow-Profile rolling stock (December 1997-August 2002)

Author’s note: while technically all narrow-profile trains and all wide-profile trains could technically run on all narrow-profile lines and all wide-profile lines respectively with a 600v DC catenary voltage (before the CBTC fitting on Line 6 and the conversion of some lines to 1500v DC, wich recieved specific dual-voltage rolling stock), lines here have trains listed only if i could find any source (photographic or otherwise) confirming that that train was actually used on that line at a certain point in time. If you have more information, especially pertaining to the 5200 Series usage on Lines 9 and 8 “old”, please do get in touch.